Women, Misinformation, and the Digital Divide

In many African towns and townships, the internet carries promise. It promises jobs, connection, visibility, and voice. It promises access to information that previous generations could not reach. But for many women, going online is not simply an opportunity. It is a negotiation with risk. A young woman in a South African township may search for employment opportunities and instead encounter scams. She may join a public conversation and face harassment. She may ration expensive data, relying on forwarded messages and screenshots rather than verified sources. For her, getting online is only the first step. The harder task is navigating digital spaces that are not always safe, truthful, or welcoming. The digital divide, for women, is not just about access. It is about power.

The Gendered Digital Divide

When we speak about the digital divide, we often reduce it to a binary: connected or unconnected. But for women across Africa, the divide is layered. It is about affordability.

It is about device ownership. It is about electricity and signal strength. It is about literacy — digital and informational. And it is about social norms that quietly shape who is encouraged to speak, and who is told to stay silent.

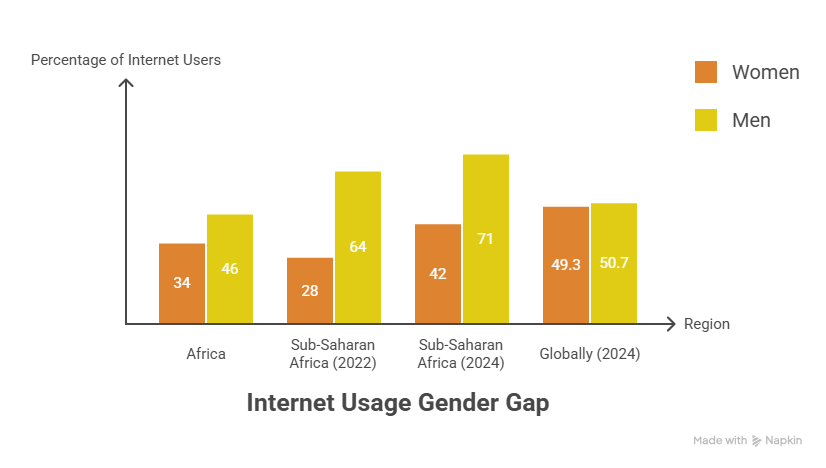

Across Africa, significantly fewer women use the internet compared to men. While the gap has narrowed in recent years, millions of women remain offline — cut off from economic opportunity, public discourse, and reliable information. Globally, the imbalance persists: tens of millions more men than women are connected. Statistics capture scale. They do not capture experience.

Some women cannot afford consistent data. Others share devices with family members. Some are discouraged from owning smartphones altogether. Many access the internet intermittently, dipping in and out rather than maintaining a steady connection. This instability matters.

When access is occasional rather than continuous, verification becomes harder. A woman who cannot search freely may rely on what arrives in her WhatsApp groups. She may not have the bandwidth — financially or technically — to cross-check a claim before it shapes her decisions. Misinformation thrives in these gaps.

When Misinformation Becomes a Gendered Weapon

Misinformation is hardly ever neutral. It often travels along existing lines of inequality. For women, false information frequently targets identity itself — their character, appearance, morality, competence. Rumours become tools of humiliation. Edited images become instruments of intimidation. Sexualised lies become methods of silencing.

Across African contexts, coordinated campaigns have sought to degrade women in politics and public life. During South Africa’s 2024 elections, reports documented how technology-assisted gendered abuse and disinformation were deployed to discourage women’s participation. Generative AI and deepfake tools now amplify these harms, making fabrication faster and more convincing. This is not accidental. It is strategic. When women are pushed offline through harassment or reputational attacks, public space narrows. Democratic participation shrinks. The digital sphere becomes less representative and less just.

Algorithms can intensify this dynamic. Systems designed to maximise engagement may promote inflammatory or sensational content, inadvertently amplifying harmful narratives about women. Without gender-sensitive moderation and accountability, digital architecture itself can reinforce inequality. In this way, misinformation becomes more than false content. It becomes a mechanism of control.

Resistance and Reclaiming Digital Truth

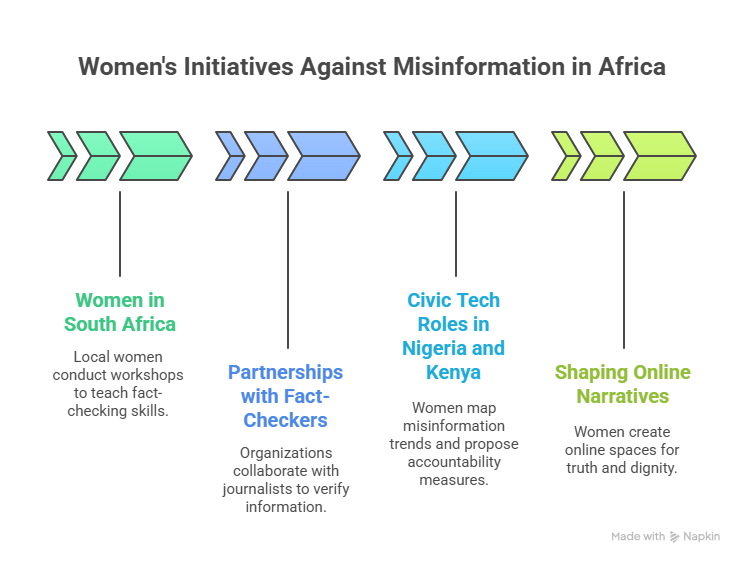

Yet the story does not end in vulnerability. Across the continent, women are building counter-spaces. In rural communities, women lead workshops teaching neighbours how to question forwarded messages and verify viral claims. Civic technologists are mapping patterns of gendered disinformation and advocating for platform accountability. Journalists and fact-checkers are localising verification in regional languages, recognising that access to truth must be culturally and linguistically grounded. These efforts are not peripheral. They are foundational. They show that women are not merely victims of digital harm; they are architects of digital resilience.

Safer Digital Futures Through Policy, Practice & Community

If we are serious about confronting misinformation, we must confront the gendered digital divide alongside it. Access must be affordable, reliable, and meaningful. Lower data costs, expanded rural connectivity, and affordable devices are not technical luxuries — they are democratic infrastructure.

Digital literacy must move beyond basic platform use. It must include the ability to assess credibility, recognise manipulation, and create trustworthy content. Programs designed with women’s lived realities in mind are more likely to build lasting resilience.

Platforms must integrate gender analysis into moderation systems, algorithm design, and harassment reporting mechanisms. Transparency about content decisions and meaningful response channels for abuse are essential. Protecting women online cannot remain an afterthought.

Policy frameworks must also evolve. Technology-facilitated gender-based violence and gendered disinformation should be recognised not merely as online nuisances, but as rights violations. Legal protections must balance free expression with the obligation to prevent targeted harm. But policy alone will not transform digital culture.

Community action — women-led digital clubs, storytelling initiatives, peer learning networks — creates spaces of trust that algorithms cannot replicate. In these spaces, knowledge circulates with care, and dignity is protected collectively.

It’s About Dignity

Too often, conversations about women online focus on deficits — what women lack, what risks they face. The deeper issue is dignity. When misinformation targets those already marginalised, it compounds existing inequalities. When women lack safe access to information and public voice, democracy itself is weakened.

Closing the digital divide is not simply about increasing connectivity numbers. It is about ensuring that when women enter digital spaces, they do so safely, with agency, and with the ability to verify truth on their own terms. Misinformation loses its power when communities are informed, included, and protected.

The goal is not only to connect women to the internet. It is to ensure the internet connects women to opportunity without exposing them to disproportionate harm. That is not a technical ambition. It is a democratic one. And it begins by recognising that digital dignity is not optional but foundational.